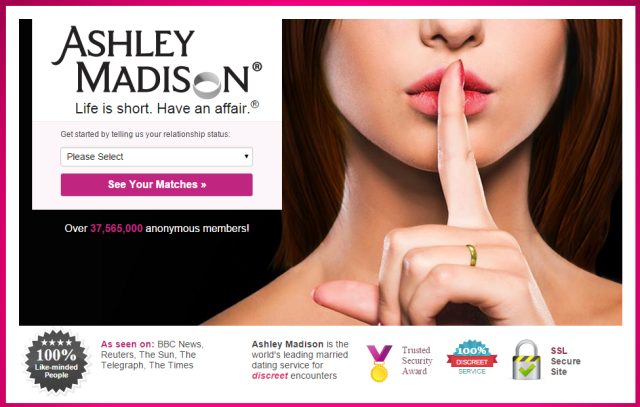

This complaint and settlement is important, but not for the obvious reasons. Yes, the breach had an outsized reach, much like the Target and Home Depot breaches preceding it. Yes, the breach involved poor security practices and deceptive promises about the site’s privacy protections. The Ashley Madison complaint follows a long line of actions brought by the FTC to combat unfair and deceptive data protection practices. The site’s exploitation of users’ desperation, vulnerability, and desire for secrecy is exactly the sort of abuse of power the Federal Trade Commission was created to mitigate.

But there are five key lessons that should not be missed in discussions about the agency’s settlement of the case. This complaint and settlement are more than just business as usual—they reflect a modern and sustainable way to think about and enforce our privacy in the coming years.

Privacy is for everyone

The hackers who published Ashley Madison users’ personal information justified their actions on the grounds that cheaters enjoy no expectation of privacy. Their message was loud and clear: “cheating dirtbags...deserve no such discretion.” The online peanut gallery chimed in with Schadenfreude. One commenter said, "Anyone who signed up to this sick site deserves everything they have coming to them."Not so fast. In pursuing this case, the FTC—in conjunction with thirteen state attorneys general and the Canadian government—made clear that everyone enjoys the right to privacy. This is true for nonconformists and conformists, the unpopular and popular. Just because the site’s users may not have endorsed mainstream values did not mean their privacy was any less worthy of protection. Privacy is owed to all consumers, no matter their interests, ideas, or identities.

Harm from a data breach is about much more than identity theft

As the Ashley Madison leak shows, data breach victims experience harm even before any personal information is used to commit identity theft. Risk and anxiety are injuries worthy of regulation. Victims of the Ashley Madison leak have an increased risk of identity theft, fraud, and reputational damage. That risk is harm in the here and now. Once victims learned about the breach, they may have been chilled from engaging in activities like house and job hunting that depend upon good credit. Individuals might have declined to search for a new home or job since there was an increased chance that lenders or employers would find their credit reports marred by theft. They faced an increased chance of being preyed upon by blackmailers, extortionists, and fraudsters promising quick fixes in exchange for data or money.

Emotional distress is a crucial aspect of the suffering. Having one’s sexual preferences and desire to sleep with strangers made public is embarrassing and humiliating. Knowing that employers, family, and friends might discover one’s intimate desires and fantasies can produce significant anxiety. An Ashley Madison user wrote, “I am absolutely sick. I can't sleep or eat and on top of that I am trying to hide that something is wrong from my wife.” Ashley Madison users who were active members of the military worried that they might face penalties because adultery is a punishable offense under the Army’s Military Code of Conduct.All of that anxiety, shame, and humiliation has led to suicide. John Gibson, a pastor, took his own life six days after his name was released in the leak. His suicide note talked about his regret in using the site. A San Antonio, Texas, police captain committed suicide shortly after his e-mail address was linked to an Ashley Madison account.

Privacy law and policy must confront the design of technologies

The FTC was concerned not just with the site’s explicit promises made to users and its mismanagement of data. The thrust of its investigation was on the failure in the actual design of the defendant’s software. This included failure to build systems that stored information appropriately, failure to ensure the buttons offered to users did what they signaled to users, and the use of vague designs like seals that gave users the false impression of the site’s legitimacy and safety.

For years, privacy law around the world focused on the kind of data collected and the activity of the people and companies that held the data. For example, most privacy laws focus on whether someone collected “personal” or “sensitive” information. That’s great, but it’s only part of the picture. The technologies that people use every day—our laptops, phones, and software—affect what we choose to disclose and how easy it is to surveil or access the information of others. For example, symbols and the design of user interfaces like the one in Ashley Madison can trick people into thinking they are safer than they really are.

These designs deceived people. The failure to architect interfaces that protected users from hackers left people vulnerable. This complaint shows how we can better incorporate scrutiny of design of hardware and software into our privacy rules instead of just focusing on what companies do with data.

The FTC’s cooperation with state attorneys general and the Canadian government is a good thing for privacy enforcement

The FTC did not develop this case alone. Thirteen state attorneys general and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada participated in the investigation. Such broad-sweeping cooperation can help harmonize privacy protections across the globe. Privacy is a global issue; cross-border information sharing benefits from such cooperation. This complaint shows how it can be done.

Of course, we cannot count on regulatory consensus going forward. State attorneys general and the FTC aren’t always on the same side, and that is a good thing. State law enforcers have nudged federal law enforcers to adopt stronger protections. The Google Do Not Track investigation demonstrates the upside of the phenomenon Jessica Bulman-Pozen and Heather Gerken have insightfully called “uncooperative federalism.”

This is the first FTC complaint involving lying bots. There will be more.

We humans are suckers for flattery. As automated software-based "bots" become easy for scammers to create and deploy, people are going to be deceived by them much more often. Bots are the future, and they are already creating problems. Dating site Tinder has been doing its best to stamp out the scourge of online bots that are attempting to flatter users into downloading apps and providing credit card information. Even bots deployed with the best of intentions are unpredictable. Microsoft’s automated chat bot Tay all too quickly reflected the worst parts of the social Internet. A Dutch man was questioned by police after a Twitter bot he owned autonomously composed and tweeted a death threat.

This case draws a very important line in the sand—bots cannot be programmed to deceive us. It is the first such complaint by the FTC that involved bots designed to actively deceive consumers. We’ll need that rule once scammers realize bots can pass the Turing test well enough to wheedle away our money and our secrets.

So while this complaint in many ways was by the books (don’t lie and always protect people’s data), it should be noted for taking a much broader and nuanced approach to privacy. That includes thinking more inclusively about who privacy is for (everyone), what counts as privacy harm (anxiety and risk), where fault lies (in design as well as data processing), how regulators should tackle privacy problems (collaboratively), and which phenomena should pose privacy issues (automation as well as databases). The Ashley Madison breach was bad, but this resolution is useful for the future.

Woodrow Hartzog is the Starnes Professor of Law at Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law and an affiliate scholar at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society.

Danielle Citron is the Morton & Sophia Macht Professor of Law at the University of Maryland, an affiliate scholar at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, an affiliate fellow at the Yale Information Society Project, and a senior fellow at the Future of Privacy Forum.

reader comments

78